We believe there is considerable potential for entrepreneurship linked to these artisanal products. The value added dairy market in India is growing at over 20% annually, with significant urban interest in niche products such as cheeses, ghees, ice creams, milk powder and so on. This growth is driven almost entirely on the back of milk production from intensively managed cow and buffalo dairies.

India also has the second largest population of goats (148 million), the third largest population of sheep (74 million) in the world, and a large number of free-ranging camels (250,000), most of them managed by pastoral communities. A tiny fraction of these populations participate in the Indian dairy market. Not surprisingly, the bulk of high-value cheese consumed in India, such as feta, is imported and sheep, goat and camel milk cheese remain largely unexplored. Equally, there have been few attempts to market a wide range of local artisanal cheeses such as the Churpi (Kalimpong) and Kalari (Kashmir), besides sweets like mawa (thickly condensed milk) and pedas (made of mawa) produced by Indian pastoralists.

While we are still at a preliminary stage, we anticipate working closely with a range of entrepreneurs to explore the potential in marketing artisanal cheeses, ghees and sweets produced by pastoral societies; goat, camel and sheep milk cheeses developed by professional cheese makers; and milk that might be sold to meet niche demand which seeks to benefit from the therapeutic values associated with goat and camel milk.

We now collaborate with Käse Cheese, a Chennai-based artisan cheese brand, to train pastoral youth in cheesemaking and to develop pastoral cheeses with milk sourced from indigenous cows, buffaloes, goats, sheep and camels in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

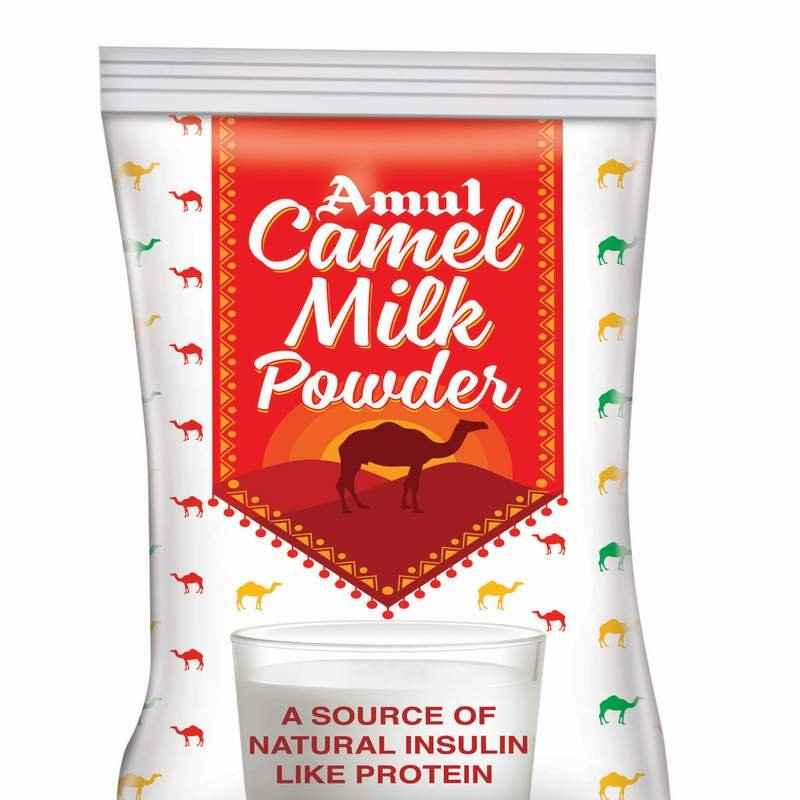

In the long run, we assume that success in this area of our work will accelerate the bulk milk procurement being undertaken by agencies such as Amul.

India also has the second largest population of goats (148 million), the third largest population of sheep (74 million) in the world, and a large number of free-ranging camels (250,000), most of them managed by pastoral communities. A tiny fraction of these populations participate in the Indian dairy market. Not surprisingly, the bulk of high-value cheese consumed in India, such as feta, is imported and sheep, goat and camel milk cheese remain largely unexplored. Equally, there have been few attempts to market a wide range of local artisanal cheeses such as the Churpi (Kalimpong) and Kalari (Kashmir), besides sweets like mawa (thickly condensed milk) and pedas (made of mawa) produced by Indian pastoralists.

While we are still at a preliminary stage, we anticipate working closely with a range of entrepreneurs to explore the potential in marketing artisanal cheeses, ghees and sweets produced by pastoral societies; goat, camel and sheep milk cheeses developed by professional cheese makers; and milk that might be sold to meet niche demand which seeks to benefit from the therapeutic values associated with goat and camel milk.

We now collaborate with Käse Cheese, a Chennai-based artisan cheese brand, to train pastoral youth in cheesemaking and to develop pastoral cheeses with milk sourced from indigenous cows, buffaloes, goats, sheep and camels in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

In the long run, we assume that success in this area of our work will accelerate the bulk milk procurement being undertaken by agencies such as Amul.